SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

|

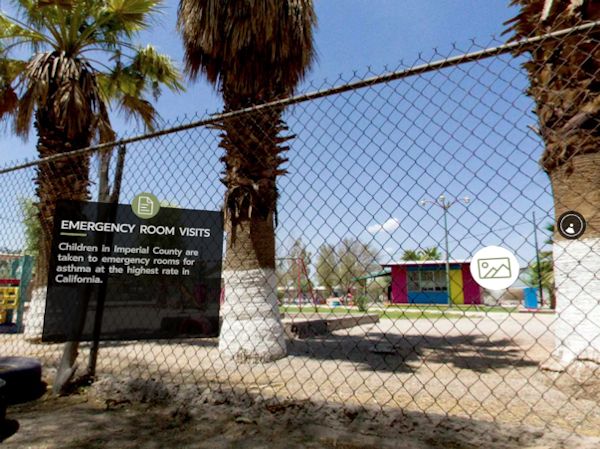

| Screengrab of a virtual reality scene exploring chronic air pollution in communities on the California-Mexico border. The feature was part of an extensive recent news package in the Palm Springs Desert Sun, part of a broader trend that is seeing more extensive coverage of environmental justice problems in news outlets. Image: Desert Sun. Click to enlarge. |

TipSheet: Environmental (In)Justice Coverage Grows, As More Media Take Note

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story is one in a series of special reports from SEJournal’s Joseph A. Davis that looks ahead to key issues in the coming year. Visit the full “2019 Journalists’ Guide to Energy & Environment” special report for more.

Environmental justice will be a bigger story in 2019 than it has been for a long time, but not because poor, minority and marginalized people in the United States will get better protections from the federal government.

In fact, the news is not that we are making big advances in environmental justice. Quite the opposite — which is why there will be so much to write about.

“Environmental justice” has been a movement for decades. What is new is that journalists are starting to cover it more.

It’s a slippery concept, but those who apply it usually argue that the politically and economically powerless do not get a fair amount of environmental protection from federal, state and local governments, nor from private companies, and that they do not get as much input into relevant decisions as the privileged.

It’s hard to wrap all this news up in a single TipSheet, because it is so many different things.

But you can be sure that under the Trump administration, environmental justice will be downgraded and de-emphasized.

President Donald Trump signalled his views on environmental justice in 2017 when he sent Congress a budget of zero for environmental justice programs at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The Interior Department, in Sept. 2018, rescinded two long-standing policy memos directing agency staff to consider the environmental justice impacts of their decisions.

Trump’s downgrading of environmental justice reverses decades of progress, however imperfect, that goes back as far as the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Federal efforts were cranked up across the board in a 1994 executive order by former President Bill Clinton.

Despite efforts, we still see daily evidence

that pollution affects the powerless

more than other Americans.

Despite efforts, we still see daily evidence that pollution affects the powerless more than other Americans. The classic examples have often involved poor rural black people in often-unincorporated areas outside town suffering from proximity to dumps whose siting they had no voice in.

For instance, coal ash from a cleanup of the earlier 2008 Kingston Fossil Plant ash spill in Tennessee was landfilled in the poor and mostly black town of Uniontown, Ala. Uniontown residents filed a civil rights complaint with the EPA, claiming the disposal was unlawful. The agency eventually rejected their complaint.

Consider these other cases:

- Reporter Ian James published a feature package in the (Palm Springs) Desert Sun earlier this December documenting how air, water and toxic pollution from Mexicali kills people on both sides of the border. Through the maquiladora factories that have sprung up, the United States has essentially exported its industrial pollution in a way that harms poor people. Those problems will linger in 2019.

- Also in December 2018, media reported a dispute over whether the poverty-plagued city of Flint, Mich., had made fast enough progress in replacing the lead service lines which had been a partial cause of the city’s toxic drinking water. Flint’s mayor bragged of good progress, but the Natural Resources Defense Council said it wasn’t enough, and residents remain distrustful. The issue might be resolved in 2019.

- Residents and businesses in rural, often poor parts of the Carolinas suffered in all kinds of ways from Hurricane Florence in September 2018. For example: the stress on the residents of Fayetteville, N.C. (subscription required), a state where some 3,863 public housing units are sited in the flood plain. Work continues on many projects to undo the flood damage (often, it’s not the first time). It will still be incomplete in many places in 2019.

- The small Appalachian town of Gary in poverty-stricken McDowell County, W.V., has a small municipal water system, but residents do not trust the multi-colored water enough to drink it. Some 38 percent of the residents there are below the poverty line, but those in Gary pay high bills for water they cannot drink. Similar stories abound in other former coalfield communities in Southern West Virginia. One hope might be a bigger federal water infrastructure program — something Congress may consider in 2019.

- As the Obama administration struggled with the utility industry over regulations to control toxic coal ash, media noted that coal-ash disposal tended to hurt disadvantaged communities more. Today, as the Trump administration further weakens coal-ash rules, environmental groups are contesting the action in court. We may see the first fruits of this lawsuit in 2019.

Problem takes many forms for varied communities

These few examples may illustrate that environmental justice (or injustice) can take many forms in the United States.

It may involve smelly landfills, toxic air pollution, hazards at refinery fencelines, eminent domain land-taking for pipelines, violation of treaties or squalid conditions for migrant agricultural workers. The year 2019 begins with many such problems unresolved.

And the communities harmed by environmental injustice are highly varied as well.

African-Americans are one often mentioned. But poor whites, Latinos, Native Americans, migrant workers, not to mention the U.S. citizens who inhabit Puerto Rico, are also differentially harmed. With today’s inclusionary politics, gender, age, ethnicity and health status come into play as well.

We also hear the term “climate justice” — an acknowledgement that the harms of climate change, and the ability to meet them, are not evenly distributed among Americans. There is even “climate gentrification.”

For instance, the Miami City Commission recently ordered a study of whether low-income residents were being priced out of their higher-elevation neighborhoods by wealthier people fleeing their flooding coastal properties.

Looking at local living conditions

One way to cover environmental justice is to keep an eye on the federal environmental justice bureaucracy — such as EPA’s National Environmental Justice Advisory Council (NEJAC) or the Federal Interagency Working Group on Environmental Justice. EPA even has a program of small grants for environmental justice work by local groups.

But the most important stories may not fall within this framework.

You may do better just by opening your eyes to living conditions for the disenfranchised in your own area. What air are they breathing? What water are they drinking?

Environmental justice has a different face in every area:

- In Texas, it may be in the unincorporated colonias along the border.

- On the Great Plains, it may be pipelines like Keystone XL crossing tribal lands.

- On Navajo lands, it may be the leftover radioactive spoil from uranium mining.

- In California’s Central Valley, it may be decrepit housing conditions or pesticide exposure for agricultural workers.

- In the Pacific Northwest, it may be harm to salmon and indigenous fishing rights.

- In Alaska, it may be the differential impacts of climate change or energy development on Native communities.

The experience of the past year suggests several reasons why environmental justice may be a bigger story in 2019.

Yes, one reason may be the Trump administration’s indifference to it. Another may be that it is actually getting worse (e.g., pipelines everywhere), or that we are expanding our notion of justice. Yet another is probably rising awareness and militancy among some disadvantaged communities.

But it also seems true that news media are covering it more. This may partly be a result of growing diversity (to the extent that there is any diversity) in the environmental journalism community itself — whether in mainstream newsrooms, cutting-edge digital natives, or investigative or niche nonprofits.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 3, No. 45. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement