SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

| An Air Force electrical systems craftsman prepares high-voltage electrical components for a power outage at Scott Air Force Base, Ill., as part of a national grid cyberattack exercise. Photo: U.S. Air Force/Daniel Garcia. Click to enlarge. |

Backgrounder: Will Hackers Crash U.S. Energy, Environment Infrastructure?

By Joseph A. Davis

The U.S. government, along with private industry, has been trying to get a grip on cybersecurity for at least two decades.

And for good reason: Experience shows the Russians are trying to work up a capability to sabotage the grid. In fact, on Oct. 4, the U.S. Justice Dept. indicted by name seven Russian military hackers for exploits that included trying to steal passwords of Westinghouse employees working to design advanced nuclear reactors.

But it’s not just the Russians. North Korea, China, Iran and civilian hackers in many countries (including the United States) are also threats.

And it’s not just about electric utilities. Cyber mischief is possible with drinking water systems, chemical plants, nuclear plants and pipelines, not to mention the whole “internet of things” (some of those “things” relate to the environment and energy beat).

It seems the first rule of utility cybersecurity is:

Don’t talk about utility cybersecurity.

This makes it especially hard

for journalists to inform the U.S. public.

So while “critical infrastructure” has been a buzz-phrase since the 1990s, what we don’t know is how effective the policy to protect has been.

That’s in part because, all along, secrecy has been part of the policy. It seems the first rule of utility cybersecurity is: Don’t talk about utility cybersecurity.

This makes it especially hard for journalists to inform the U.S. public about whether Russians or other bad actors could black their electrical grid out or could cause some other infrastructure disaster.

Yet journalists owe an accounting to their audiences. This Issue Backgrounder should help you get the background and resources to start telling the story.

Attacks on electric grid a reality

Let’s start with the electrical grid. The U.S. and Canadian grid works only because of delicate coordination of large arrays of power sources and power demands across large geographic regions. Information sharing and remote control are essential to grid management. Timing is key. It’s like a trapeze act.

Under those circumstances, a hacker blackout is not a paranoid fantasy. For instance, on December 23, 2015, the Russians took down part of Ukraine’s electric grid with a complex and sophisticated cyberattack.

It was a very loud wake-up call. Subsequent analysis suggests that Russia is much more capable of launching — and willing to launch — such attacks than we thought they were.

More chilling — and closer to home — were some partly successful Russian cyberattacks on parts of the U.S. grid, beginning as early as March 2016, that the Department of Homeland Security revealed in March 2018.

The Department of Homeland Security put out an official alert, the first in a series, about this on March 15, 2018. The alert warned of “Russian government actions targeting U.S. Government entities as well as organizations in the energy, nuclear, commercial facilities, water, aviation, and critical manufacturing sectors.”

It stopped short at first of reporting actual sabotage, though.

Homeland Security and the FBI reported “a multi-stage intrusion campaign by Russian government cyber actors who targeted small commercial facilities’ networks where they staged malware, conducted spear phishing, and gained remote access into energy sector networks.”

They went on: “After obtaining access, the Russian government cyber actors conducted network reconnaissance, moved laterally, and collected information pertaining to Industrial Control Systems (ICS).”

Russian hackers hit nuclear plant

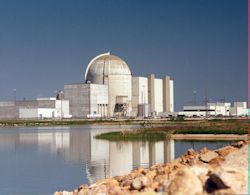

|

| Wolf Creek nuclear power plant near Burlington, Ks., where Russian hackers found their way into the computer system. Photo: Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Click to enlarge. |

The most frightening part is that the Russian hackers found their way into the computer system of a nuclear power plant — the Wolf Creek plant near Burlington, Kansas, which is owned by three different utilities.

The intrusion apparently did not reach control systems, according to Homeland Security and the FBI, and was “limited to administrative and business networks.”

But the problem for journalists and the public is that the government’s reflex reliance on secrecy makes the reassurances hard to confirm or believe.

Subsequent alerts during 2018 showed that despite having the whistle blown on them, the Russian hacker intrusion attempts were continuing.

The DHS office issuing the alerts was the U.S. Computer Emergency Readiness Team — whose site is worth visiting to stay current if you are covering cybersecurity. It includes lots of useful advice for securing computer systems of ordinary enterprises, not just utilities.

One reason the feds shared this information: Utilities must know of threats they face if they are to take them seriously enough to protect themselves. At the same time, too much disclosure could help the hackers.

In practice, since the late 1990s, a non-public information sharing network has grown up connecting utilities and federal security agencies (more on that below).

A window into intrusion tactics

What has been revealed by these intrusion attempts, and successes, are some of the tactics and strategies the hackers use.

They first attack the most vulnerable part of the systems: humans. Hackers stage their campaigns, working from less well-defended peripheral parts of a system to gain the trust and credentials they need to get into the critical core systems.

They may, for example, start with third-party contractors or suppliers of the government agency or utility they seek to penetrate.

They may start with “spear-phishing” — which includes a broad array of tricks that typically uses email to lure a targeted individual to reveal a password or other personal information. Often the email is cleverly disguised (for example a job ad seeking computer system engineers).

“Phishing” is the word for mass-mailed efforts to seduce victims, while spear-phishing efforts usually target specific individuals.

Hackers then use these peripheral systems to harvest credentials (because they may be trusted) or to store and install malware (such as programs that steal passwords by logging keystrokes). Eventually, they use these positions to launch attacks on the central target — which could well be a power plant control room.

Another point of vulnerability — industrial control systems

The control rooms that run power plants — or electric grids for that matter — are really just one kind of target. There is another.

The 2018 US-CERT alert revealed that Russian hackers had also gone after U.S. government entities, “as well as organizations in the energy, nuclear, commercial facilities, water, aviation, and critical manufacturing sectors.” Many of these use what are called “industrial control systems” (requires subscription).

The term “industrial control system” can refer to almost any mechanism for remotely controlling machinery of some kind. Electric grids, pipelines, railroads and the like are physically spread out but require intelligent central control. This usually happens through some kind of data or communications network.

Stuxnet malware may have infected

mechanisms at an Illinois water utility in 2011,

although full details are shrouded in mystery.

Hacking industrial control systems is feasible. The Stuxnet worm that damaged Iran’s uranium enrichment centrifuges during the years before 2010, when it was discovered, is said to have been developed jointly by the United States and Israel.

One thing: Once the malware was released into the wild, it took root in some non-target systems. It may have infected mechanisms at an Illinois water utility in 2011, although full details are shrouded in mystery. Water systems remain vulnerable.

The Stuxnet exploit taught another lesson: You can hack a system even when it is not connected to the internet. Critical systems often use the “air gap” defense — literally disconnecting from the internet. But a rogue thumb drive, used carelessly, can transmit all the malware needed to attack a system.

How vulnerable U.S. electric utilities really are remains unclear. An alert issued in July 2018 said Russian hackers had penetrated U.S. electric utility control rooms to the point where they could actually “throw switches.” But a week later, U.S. officials tried to walk back that account.

Where do we stand? How do you know?

Should we worry about grid cybersecurity? The short answer is “yes, a lot.”

The problem is we — the media and the public and probably the government as well — don’t know all there is to know.

|

| Karen Evans, center, sworn in as assistant secretary of cybersecurity last August. Soon after, she testified she did not feel confident that the U.S. electric utility industry is ready for a serious cyberattack. Photo: Energy.gov. Click to enlarge. |

Cybersecurity seemed to remain a priority during the early, chaotic days of the Trump administration. President Donald Trump signed an Executive Order (EO 13800) telling all federal agencies to pull up their socks on cybersecurity. Most had already been trying.

Like most executive orders, it gave Trump a sure photo-op but didn’t actually make much happen. As the year dragged on, it was clear that it mostly amounted to paperwork and was falling behind schedule.

If cyber was in fact a national security issue, it was muddled by White House chaos. By April 2018, on the second day of John Bolton’s tenure at the National Security Council, the top cybersecurity adviser on the NSC staff, Tom Bossert, had resigned (requires subscription).

One starting point: Karen Evans was installed in Sept. 2018 (requires subscription) as the Energy Department’s assistant secretary for cybersecurity, energy security and emergency response.

In a hearing the same month, she told House members (requires subscription) she did not feel confident that the U.S. electric utility industry is really ready for a serious cyberattack. Utilities, on the other hand, have expressed confidence (requires subscription) that their cyber defenses are sound.

Leveraging fear to tilt policy, markets

Cybersecurity is much like a multidimensional, asymmetrical game of chess. It is always worth remembering that a lot of what we don’t know resides with the U.S. Cyber Command, which is very secret because it is lodged within the military and intelligence agencies, but which is also involved with protecting civilian infrastructure (requires subscription) and offensive operations.

Since one aspect of cyber conflict is bluffing, intimidation, deception, and social and political manipulation, other countries who actually attacked the U.S. grid could expect massive retaliation in kind. DHS Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen said in Sept. 2018, that the attackers would find it was “not a fair fight” (requires subscription).

Fear is certainly one of the weapons in cyber conflict. But reporters need to remember that weaponized fear and uncertainty serve the political goals of many players. Fear is used to justify secrecy. And secrecy is used to protect private industry (and its profits) from regulation and accountability.

Energy Secretary Rick Perry campaigned

to use cybersecurity threats to justify

the Trump administration’s efforts to tilt

U.S. electricity markets toward coal and nuclear.

A pertinent example is Energy Secretary Rick Perry’s campaign to use cybersecurity threats to justify the Trump administration’s efforts to tilt U.S. electricity markets toward coal and nuclear. Perry’s ostensible rationale is that coal and nuclear plants are more secure because their fuel is onsite, whereas gas from pipelines (requires subscription) faces cyber vulnerabilities.

The problem with this argument is that nuclear plants have inherent security problems, and once the electricity is on the transmission grid, it is all equally vulnerable. Experts have said that even with bailouts, the grid will be vulnerable to cyberattack.

Expect the White House to tell us to be very afraid, but pay heed (requires subscription) to how they want to fix the problem. Ask who profits. Stay aware of how much power goes to Department of Energy.

Who else benefits from fear? We have to mention the IT industry, which makes a lot of money protecting everybody from cyber-threats. But don’t be too cynical; they may prove good sources.

When false trust is a weapon, trust itself is a two-edged sword. A few years ago the virus protection company Kaspersky had a golden reputation and a large share of the security market. Nobody seemed concerned that it was Russian-owned, or that it had links to Russian intelligence.

More recently, U.S. intelligence agencies, worried that Kaspersky software was a potential backdoor for Russians, pulled the plug on its use by federal agencies.

Knowing the ‘grown-ups’ in the room

It is critical to have federal leadership that understands the problems and takes them seriously.

|

| A cyber-attack simulation with the 112th Cyberspace Operations Squadron at Horsham Air Guard Station, Pa., January, 2017. Photo: U.S. Air National Guard. Click to enlarge. |

At the July 16, 2018, Helsinki summit, Russian President Vladimir Putin re-proposed the idea of a joint U.S.-Russian task force to investigate Russian cybermeddling in U.S. elections. It was an idea that had previously been laughed off by the cybersecurity community.

The problem: Trump expressed approval of the idea. It is not known whether anything came of it, because Trump never revealed the content of his meeting with Putin. The only saving grace seems to be an intelligence and national security establishment willing and able to act as the grown-ups (may require subscription) in the room.

If you are covering electric grid cybersecurity, it is good to know who else are the grown-ups in the room (at least supposedly).

For instance, the North American Electric Reliability Corporation, or NERC, is in charge of preventing grid failures of many kinds. There have been many. NERC links up with the various regional grids, and works in collaboration with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, or FERC.

Chastened by the Northeast blackout of 2003, which affected some 53 million people in the U.S. and Canada, Congress strengthened NERC in the 2005 Energy Policy Act, making it truly binational. While much info can be gleaned from a hawk-eyed monitoring of the NERC website, the problem for reporters and the public is that NERC remains both opaque and secretive about many things.

Homeland Security, Energy on cyberwatch?

The Department of Homeland Security and the Energy Department could also be defenders against cyberattacks on the U.S. grid. Only further evidence will tell, however, whether this potential is realized.

Congress appears close to sending President Trump a bill (HR 3359) that would ensconce Homeland Security as the key agency for civilian cybersecurity.

The department is not known for transparency. The question remains whether all this is just optics. More information is here and here.

So if Homeland Security is the key agency, why all the drumrolls and flourishes about Karen Evans’ installation? One headline called her a “cyber czar” (requires subscription). The Energy Department created its own brand-new cyber office just for her.

There may be many answers — including turf (requires subscription), optics and just possibly a strong White House interest in keeping alive the cybersecurity argument for its coal bailout. In practice, the Homeland Security may deal more with the electric grid and Energy with pipelines.

But what we saw in August and September 2018 was the creation or upgrading of two new civilian cybersecurity agencies, with the new rising-to-prominence of leaders, and Congressional hearings marked by earnest declarations.

To that was added other agencies. In response to earlier Homeland Security warnings (requires subscription) about Russians hacking U.S. nuclear plants, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (requires subscription) in August issued a “Regulatory Guide” telling utilities what it expected from them in cybersecurity.

Who’s minding pipeline security?

So what about pipelines — the linchpin in the Trump case for subsidizing coal? Pipeline failures can kill people and cause environmental damage. To the degree that they are regulated at all, they are regulated by the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, or PHMSA, within the Department of Transportation.

Right now, though, the “security” of pipelines falls under the authority of another agency — the Transportation Security Administration within DHS. PHMSA in 2016 issued cybersecurity guidelines for pipelines that were voluntary. TSA has issued its own guidelines.

There is ongoing controversy over

who should safeguard pipeline cybersecurity. ...

The unspoken secret is that, because of their layout

through remote areas, pipelines are inherently indefensible.

That is hardly the end of it. There is ongoing controversy over who should safeguard pipeline cybersecurity. FERC, which does the licensing of interstate pipelines, seems to think the job should go to the Energy Department. The new rationale is that gas is critical to the electric grid.

Few among the media and public are jaded or wise enough to see how political this is.

“To date,” wrote Bloomberg reporter Rebecca Kern in June 2018, “Homeland Security is unaware of any confirmed or validated cyberintrusions that penetrated a pipeline industrial control system and led to a physical impact, a department official who spoke on condition of anonymity told Bloomberg Environment.”

The biggest danger to pipelines, statistically speaking, is shoddy construction, neglected maintenance, lax regulation, backhoes or operator error.

But if you want to sabotage one, you do not need to be a cyber-genius. A .50 caliber sniper rifle will do it. The unspoken secret is that, because of their layout through remote areas, pipelines are inherently indefensible.

Track key players — the utilities

In the end, the most important players (and sources) on grid cybersecurity will include the utilities themselves. They may not tell you much, because they don’t have to.

It will make sense to follow your state’s public utilities commission (whom they do have to tell things to). But you will also need to use your journalistic skills to cultivate utility sources. They do care, mostly. Politically, the utility industry has been known to dominate the federal agencies that are supposed to oversee it.

Behind the bureaucracy, utilities are key actors. NERC is one place where they are influential. But for decades, there has been an apparatus for utilities and the government to share threat information — called the ISAC — Information Sharing and Analysis Center.

ISAC dates back to the early days of the federal anti-terrorism effort in the late 1990s and was established under executive authority by former President Bill Clinton.

Each “critical infrastructure” sector has its own center. The one for the electric sector, for instance, is called E-ISAC and it is operated by NERC. Each center functions as a two-way sharing channel for threat information, although the public and press can usually not get access to the information.

Parts of the federal government have taken grid cybersecurity seriously (requires subscription) for some time. With or without help from its Russian cyberallies, the Trump administration this fall tried to show it took grid cyberthreats to heart, especially nuclear ones.

Confusion over who is running cyber strategy

One symbol of this effort was an administration-wide cyber strategy released Sept. 20, 2018. That strategy came from the White House, apparently with input from National Security Advisor Bolton.

Not surprisingly, it emphasized retaliation (requires subscription) for any attacks on the United States through offensive cyber operations (may require subscription). This makes the Defense Department (requires subscription), the Cyber Command, and similar agencies, the key players.

If you are confused about who is running the show, you are not crazy. We have not even talked about the role Congress plays in grid cybersecurity. Senate Energy Committee (requires subscription) leaders have held hearings to express concern, as have several other panels. Each has focused on a different facet of the challenge.

Something to keep in mind: each Congressional panel has jurisdictional ties (and a kind of “sponsorship” stake) with a different family of federal agencies — and different business interests and agendas.

One thing, though, has come clearly into focus. The year 2018 saw a crisis of concern about cyberattacks on the U.S. electric grid. What seemed to make the bells ring was that it was the Russians, and they targeted nuclear plants, and they succeeded to some extent. And that government agencies admitted it in public.

For several reasons, it was also the year when various parts of government tried to do some things to address the threats — or to appear to address them, whether or not a successful defense was actually mounted.

But those government actions only raise further questions. Do the many different agencies have different motives? And are they more motivated by what is good for the agency than by what is good for the public?

What is the solution, then? Do we have to wait for a disaster?

It might be that large, secret, top-down federal cybersecurity programs are not the total answer — any more than large, centralized, automated electric grids are the answer.

Whether the threat is hurricanes, ice storms or hackers, decentralized and resilient electric systems (buzzword: “microgrids”) may be less prone to large failures — as well as ways to support renewables.

Information sources to report the story

Some useful information sources on grid cybersecurity may include:

- North American Electric Reliability Corp.

- Electricity Information Sharing and Analysis Center (E-ISAC, part of NERC)

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission

- Energy Department Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response (CESER)

- Dept. of Homeland Security, especially the Office of Cybersecurity and Communications

- DHS Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT)

- Edison Electric Institute

Publications that are informative on grid cybersecurity include, first and foremost, the E&E family of publications, such as EnergyWire. Reporters Blake Sobczak and Peter Behr cover cybersecurity like the dew, and much of their work is outside the paywall.

Utility Dive, which covers all aspects of the industry, and whose content is mostly open, is also authoritative. Inside Cybersecurity may help — it has a soft paywall. Some parts of the Bloomberg empire do a good job also. Bloomberg’s New Energy Outlook is good. Wired magazine, written by geeks and for geeks, is interested in cybersecurity, interesting and authoritative, and its content is often open.

Then there are subscription-based trade publications like CSO, SC Media or Information Security Buzz, parts of which are open.

Another potential source of information is the private cybersecurity firms which interact with both the government and utilities. We are not going to start naming them, since the ones left out will complain. Some of the big ones are obvious.

Be careful, though, because they may tell you the crisis is dire and that they have the solution. They make money doing this.

Joseph A. Davis is a freelance writer/editor in Washington, D.C. who has been writing about the environment since 1976. He writes SEJournal Online's Issue Backgrounders and TipSheet columns, directs SEJ's WatchDog Project and writes WatchDog Tipsheet and also compiles SEJ's daily news headlines, EJToday.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 3, No. 39. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement