SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

|

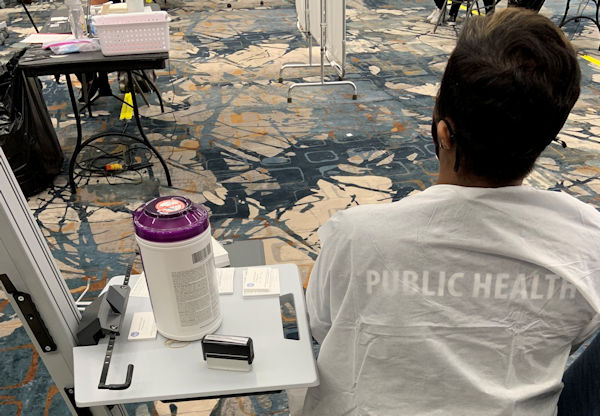

| U.S. public health infrastructure has been diminished over time, well before the current pandemic. Above, vaccinations begin at Bojangles Coliseum in Charlotte, North Carolina, on Jan. 5, 2021. Photo: Mecklenburg County, Flickr Creative Commons. Click to enlarge. |

TipSheet: Public Health Infrastructure Emerges As Critical Environmental Story

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story is one in a series of special reports from SEJournal that looks ahead to key issues in the coming year. Visit the full “2021 Journalists’ Guide to Energy & Environment” special report for more.

By Joseph A. Davis

Chances are you don’t want rat droppings on the floor of your favorite restaurant. Congratulations! You believe in public health. Your county health department likely inspects restaurants and is required by law to report its findings to the public. This is not supposed to be controversial.

As we undergo the worst pandemic in a century, environmental journalists may (or not) realize that they are doing public health work. Environmental health is an important branch of public health, and informing the public is an essential public health action.

Over the past century or two, a vast and complex structure of laws, rules, government agencies, hospitals and health-care providers has grown up to prevent or reduce diseases that may sicken or harm people on a large scale. Call it our public health infrastructure.

Before the pandemic, news media gave comparatively little attention to the nation’s public health infrastructure. That may have been a mistake.

There was little outcry or pushback when the

Trump administration started proposing draconian

cuts in funding and personnel at public health agencies.

There was little outcry or pushback in 2017 when then-President Trump’s administration started proposing draconian cuts in funding and personnel at public health agencies. The problem was worsened by the fact that the public health infrastructure had been starved and downgraded for decades before Trump.

So rebuilding, fortifying, upgrading and bomb-proofing (or idiot-proofing?) the nation’s public health infrastructure is one of the most important things incoming President Joe Biden could do. There are signs that he may try.

In any case, it will be a crucial story that environmental journalists will have on their plate in 2021.

Public health agencies numerous

Many governmental agencies are engaged in public health, just at the federal level.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, is the keystone. It maintains surveillance of threats, compiles and issues statistics and scientific information and prescribes guidelines for protecting public health.

Whatever its shortcomings, the CDC is often described as the “gold standard” for public health agencies around the world. (Check out their offerings on environmental health.)

That’s just the start. Dr. Anthony Fauci, at the forefront of public messaging on COVID-19, heads the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. NIAID is under the research-focused National Institutes of Health, which also includes the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (an outfit environmental journalists also need to know about).

Then there is the U.S. Public Health Service, which is the locus for a quasi-military commissioned corps of health professionals from all over the federal government. They can be called up during emergencies and are overseen by the surgeon general.

Also essential is the Food and Drug Administration, which scientifically rules on food safety and the safety and efficacy of drugs. The FDA is the agency that is approving COVID-19 vaccines. It is one of several public health agencies under the Department of Health and Human Services. The HHS Secretary has been a key player under Trump.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency also has a vital role in public health. You may never have heard of the Health Resources & Services Administration, but it delivers all kinds of support to local health agencies. That includes community health centers, which provide health care to many hard-to-reach localities.

Equally important in the public health infrastructure are state public health agencies and local ones too (typically organized at the county or city level). Hospitals and medical practices are part of it, too — along with everything including the school nurse.

Is infrastructure hollowed out?

Some say this extensive public health infrastructure has been hollowed out — and has strained and faltered at the time (during a pandemic), when we need it most. That may be a rather sweeping generalization about a vast and complex system. Is it half-empty or half-full?

A 2016 article in the American Journal of Public Health found that U.S. public health spending rose between 1960 and 2008 — but then dropped 9.3 percent by 2016. And an in-depth investigation by Kaiser Health News and the Associated Press found that public health spending has continued to drop in more recent years.

The lede: “The U.S. public health system has been starved for decades and lacks the resources to confront the worst health crisis in a century.” Other studies agree.

The damage from politicization may prove

long-term, because it has reduced public trust

in the advice of public health experts and scientists.

Worse destruction to the public health system has possibly come from politicization, which reached new lows (may require subscription) under Trump. The damage may prove long-term, because it has reduced public trust in the advice of public health experts and scientists.

The news media have played some role in this, as it broadcast live (may require subscription) and unfact-checked hours of Trump downplaying the COVID-19 pandemic’s gravity, as ranks of public health officials stood largely silent behind him. Eventually (once the election was over), Trump abandoned even the pretense of leadership and left the states and hospitals to struggle on their own.

Messaging critical during outbreaks

Experience teaches that part of a successful response to outbreaks is finding them fast and attacking them fast with public health measures like testing, contact-tracing and masks. And good messaging.

The Obama administration learned some of these lessons the painful way in 2009 when confronted with the H1N1 virus. It turned out that the Obama-Biden administration had left what it had learned in a “pandemic playbook.” The Trump camp denied that it existed and blamed Obama for leaving it no guidance.

Obama also left Trump a pandemic response team within the National Security Council apparatus. The Trump administration disbanded it in 2018.

Remember Trump promising vaccines before the election? Well, there have been a lot of promises, but now that vaccines are starting to arrive, the pace of the actual rollout, getting shots into arms, appears to be lagging way behind. There seems to be little federal involvement once they are delivered to the states.

Even before he enters the White House in 2021, Biden has signalled that COVID-19 response is a top priority. One of his first personnel announcements was of a health team of seasoned, science-based professionals, with Dr. Fauci at the center of it. It will be enough if they can minimize suffering and get us to the end of this pandemic.

But news media should be on the watch for actions to prepare us better for the next one (or the “Big One”). The emergencies chief at the United Nations-linked World Health Organization recently put it this way (may require subscription): “This pandemic has been very severe. It has affected every corner of this planet. But this is not necessarily the big one.”

With a lot of suffering and death (and vaccinations), most Americans will get through this COVID-19 pandemic. Events have shown we were not really ready for it. Now is a good time to ask whether we are ready for the next pandemic, and what we must do to prepare.

And reporters should watch, too, for whatever the Biden administration and Congress may do to inoculate the government’s public health apparatus against all the missteps of the Trump era. Funding of programs. Integrity of science. Effective surveillance. Planning and preparedness. Leadership and collaboration. Open and transparent information.

Story ideas

It is worth noting that the public health story goes beyond the immediate pandemic and the federal response to it. Rebuilding and improving the public health infrastructure is worth covering before the next one hits. Here are some COVID-19 and other angles to explore:

- What is the funding history of your state or local public health department? Is it enough? Who runs it? Is it political? How has it responded to the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Looking at your state, how much testing has there been since the pandemic started? When did it happen? Is it enough? Is it easy to access?

- What has been the “curve” of infections in your state or area? Hospitalizations? Deaths?

- Are public health decisions (e.g., masking mandates) in your area made by partisan politicians or by public health professionals?

- How has the vaccine delivery (into arms) been going in your state or locality?

- What have your public health agencies done to plan and prepare for the next pandemic or public health challenge? (Hint: The next challenge could be a toxic release or environmental pathogen.)

Reporting resources

- American Public Health Association: This professional association works well with media.

- Emerging Infectious Diseases: This CDC science monthly is for epidemiologists, so at first it may read like a science journal. But once you understand it, it may inspire you to write a news article (or a horror movie script).

- Public Health Institute: This nonprofit works in the United States and globally on a wide range of public health challenges, not just pandemics.

- Johns Hopkins COVID-19 Dashboard: Good statistics — likely more reliable and current than anything you can get from the federal government.

- Best Public Health Schools: A good source of schools with experts who are science-based and don’t (usually) have political axes to grind. You may find local experts with local angles.

- Alliance for Health Policy: A nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank that maintains handy lists of experts.

- World Health Organization: An offshoot of the U.N., this organization has offices in over 150 nations and includes most of the nations in the world. Despite Trump’s badmouthing, they can give good information on global pandemics.

Joseph A. Davis is a freelance writer/editor in Washington, D.C. who has been writing about the environment since 1976. He writes SEJournal Online's TipSheet, Reporter's Toolbox and Issue Backgrounder, as well as compiling SEJ's weekday news headlines service EJToday. Davis also directs SEJ's Freedom of Information Project and writes the WatchDog opinion column and WatchDog Alert.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 6, No. 2. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement