SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

|

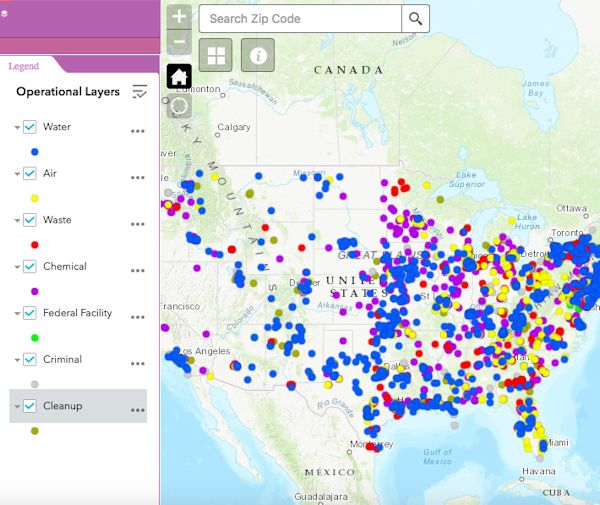

| A U.S. Environmental Protection Agency map showing information on concluded enforcement actions and cases from fiscal year 2017. Image: EPA. Click to enlarge. |

TipSheet: Will the Downturn in Environmental Enforcement Continue in 2019?

EDITOR'S NOTE: This story is one in a series of special reports from SEJournal’s Joseph A. Davis that looks ahead to key issues in the coming year. Visit the full “2019 Journalists’ Guide to Energy & Environment” special report for more.

One critical story to watch in 2019 is environmental enforcement, not just with a magnifying glass on the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, but with a broader lens on other federal agencies and in every U.S state, where in some cases it is a disaster getting worse.

As the Associated Press just reported on January 15, EPA criminal actions against polluters reached a 30-year low in 2018.

And as 2019 progresses, it will show us the third straight year of environmental enforcement under Trump — likely confirming that a downward trend in the administration’s first two years was no statistical fluke. Fewer and fewer of the cases will be ones started under the Obama White House, so the Trump era trends will stand out in sharper relief.

That pattern showed itself quite early. New York Times reporters Eric Lipton and Danielle Ivory did a deep dive on EPA enforcement (may require subscription) on EPA enforcement back on Dec. 10, 2017.

Their findings: “An analysis of enforcement data by The New York Times shows that the administration has adopted a more lenient approach than the previous two administrations — Democratic and Republican — toward polluters.”

EPA has not yet issued its usual annual report on enforcement statistics (the new one would be for fiscal 2018; last year’s was issued in February). But whenever it does comes out, the 2018 report will be news.

The EPA tends to spin its

enforcement reports in its own favor.

But there are other reports

that tell a different story.

The EPA tends to spin its enforcement reports in its own favor, making the agency look like a tough cop. But there are other reports — from advocacy groups and news media — that tell a different story.

And there are investigations pending to answer the question of why the numbers are so low. One is being conducted by EPA’s own internal watchdog, the Office of the Inspector General. Another is being done by Congress’ nonpartisan Government Accountability Office.

Predicting completion of such probes is dicey, but both could see published results in 2019, and both could be news.

Data sources allow for closer look at enforcement numbers

If you want to report this story there are plenty of numbers.

For instance, the AP investigation used data compiled by the watchdog group Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, or PEER — apparently via the Department of Justice and EPA.

And the database of enforcement actions the Times built for its data journalism project was based on some publicly available data sources you can access yourself. The Times explains its methodology here (may require subscription).

If you are working this story at the state or local level, you will want to get familiar with EPA’s ECHO (Enforcement and Compliance History Online) database. While not always up to date, it is online, searchable and pretty good.

Among the nonprofit advocacy groups that track EPA enforcement is the Project on Government Oversight. It does its own analysis of EPA figures, adding in data from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse.

Another source is the unique group, the Environmental Data & Governance Initiative, a collaborative that was formed to watchdog EPA at the start of the Trump administration. It issued a report about EPA enforcement in Nov. 2018 titled “A Sheep in the Closet: The Erosion of Enforcement at the EPA.”

One of the best nonprofit watchdogs is the Environmental Integrity Project, or EIP, founded and headed by Eric Schaeffer, who was himself a top EPA enforcement official during the Clinton-Bush years. It too issued a report on the drop in civil enforcement under the Trump EPA back in August 2017. EIP completed another report in February 2018, noting that civil penalties against polluters had dropped by half during Trump’s first year.

Looking at enforcement beyond EPA

Remember that EPA is not the only agency doing environmental enforcement.

For example, the Interior Department’s Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement is supposed to police discharges of oil from offshore rigs. It does offer some data on its enforcement actions.

Another example is the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which enforces a variety of conservation laws, such as the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

You will find other kinds of enforcement at energy agencies such as the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission or the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration enforces its own workplace rules, which often involve environmental exposures.

Your state environmental enforcement agency

is likely to be the starting point

for many regionally relevant stories.

Authority to enforce many federal environmental laws has been delegated to the states and tribes. Your state environmental enforcement agency is likely to be the starting point for many regionally relevant stories. You can find lists of state agencies (plus, here). At the state level, cases are actually prosecuted by the state’s attorney general.

Keep in mind that criminal cases are not the only measure of enforcement. Many cases are civil, and many never get to court. In some cases, the polluter or violator simply changes behavior and complies with the law — because of EPA intervention, of course.

Some cases are settled voluntarily after negotiation, in the form of consent decrees approved by some court. Often, what EPA seeks is a cleanup, or installation of pollution control equipment — rather than simply fines as penalties.

For actual prosecution, EPA (and other agencies) refers cases to the DOJ and its Environment and Natural Resources Division. The ENRD finally got a Senate-confirmed non-acting head, Jeffrey Bossert Clark, on Nov. 1, 2018, almost two years into the Trump administration.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 4, No. 4. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.