SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

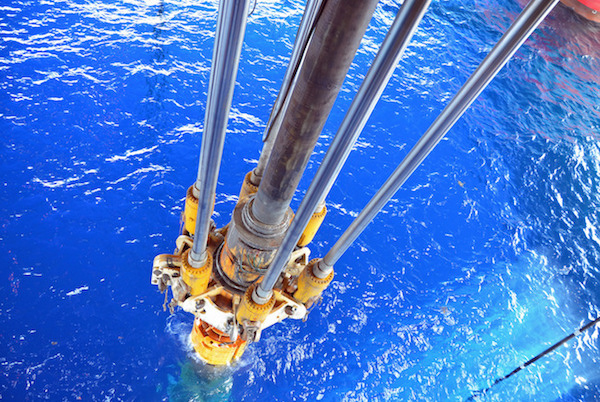

| Election of Congressional candidates in 2018 may depend on how hard they run against President Donald Trump’s offshore drilling plan. Above, drilling equipment below a semi-submersible rig in deep Gulf of Mexico waters. Photo: Jennifer A. Dlouhy/Houston Chronicle), Flickr Creative Commons |

Backgrounder: 2018 Elections Could Be Game-Changer for Environment, Energy

By Joseph A. Davis

This special Backgrounder is one in a series of special reports from SEJournal’s Joseph A. Davis that looks ahead to key issues in the coming year. Stay tuned for more in coming weeks and for the full “2018 Journalists’ Guide to Energy & Environment” special report in late January.

The 2018 elections may prove more consequential for environment and energy policy than any for a long time. They could drastically slow the deregulatory campaign of the Trump-GOP regime — or even reverse it.

We won’t know until November, but before then journalists can help voters frame the choices they face. Imagine for a minute that party control changes in the House or Senate — or both. The legislative implications would be enormous.

|

Such a change would also bring within range impeachment of President Donald Trump. Although Democratic leadership currently downplays that idea, flipping House and Senate would change that — and impeachment could be more plausible if Special Counsel Robert Mueller comes up with smoking guns. Serious Congress members are already seriously pushing impeachment.

Removal of Trump would not mean an end to GOP control of the White House. It might, however, result in an eventual change in some of the more extreme anti-environment and pro-fossil-fuel policies from the executive branch.

Regulatory, judiciary impacts uncertain

But the ship of state does not turn quickly. Trump appointees would remain atop many agencies, and the policy and regulatory machinery would still grind forward in many cases.

Environmental issues aren’t necessary for Congress to change hands. That could well happen anyway. Current polling and some special election results suggest strongly that Dems could win control of the House, and possibly the Senate in 2018. This is what many experienced and respected political pundits are currently saying.

One caveat: talk of a Democratic “wave” in 2018 is based on conditions right now, and those conditions could change in ten months (in either direction). But Republicans are scared right now and that alone could change the stance of Congress.

One consequence of the current GOP lock is that

Trump can appoint strongly anti-environmental judges

and see most of them confirmed.

One consequence of the current GOP lock is that Trump can appoint strongly anti-environmental judges and see most of them confirmed. Trump has already made some mark on the judiciary — with Neil Gorsuch at the Supreme Court, for example — an impact that may be lasting on some climate cases.

But many more appointments are yet to be made and many more seats not yet vacant. As the Trump administration grinds on, more and more policy questions are likely to be decided in the courts. How long Trump remains in office, and how long Republicans keep the Senate, are variables that will determine how deep Trump’s impact on the courts will be. Timing is everything.

With Democrat Doug Jones’ election in Alabama, the GOP margin in the Senate is even thinner. It serves as a reminder that the minority can have huge power to stop things in the Senate. Already Dems like Florida’s Bill Nelson are plotting to use legislative power to block Trump’s offshore drilling plan.

A number of obscure tools are handy in a closely divided legislature — most importantly appropriations. A note, though: The Congressional Review Act (used so successfully for regulatory rollback during Trump’s first months) will not be an available tool for Democrats to undo new Trump rules, since Trump can still veto CRA overrides.

Latino voters concerned about environment

As the U.S. electorate changes, Latino voters have manifested a demographic surge that will have increasing impact on many elections. This impact will not be evenly distributed geographically (more in Southern California, less in North Dakota).

Polls in 2015 and later revealed a strong pro-environment predilection among Latino voters that might have surprised some people: Concern about the environment was virtually as strong as concern about immigration. These numbers have held up since Trump was elected.

Among the many possible reasons for this, one stands out: Latinos often live in places and conditions where environmental pollution is a problem and harms them. This is not lost on mainstream environmental groups. They have been working to organize and appeal to Latino voters.

While Latino voters are still a minority in many places, their strong pro-environment leaning can make an important difference in close races. Their influence — and turnout — could matter a lot in states like Nevada, Arizona, Colorado and Florida.

The League of Conservation Voters, possibly the most powerful green electioneering group, has built a CHISPA program that reaches beyond those states to Latino communities in New Mexico, Maryland and Connecticut.

Environmental justice concerns spread

The December 2017 special election in Alabama to fill a Senate seat offers another lesson: African-American voters, when motivated, are powerful enough to score upsets (usually for Dems).

Likewise, African-American voters energized by the Klan rally in Charlottesville have been credited with helping win Virginia’s November governor’s race and to almost win the Virginia House of Delegates. There is some evidence that black opposition to Trump was a factor in this.

The question is whether environment and energy

issues will energize black voters in ways

politicians will perceive as powerful.

The question is whether environment and energy issues will energize black voters in ways politicians will perceive as powerful. Emily Atkin at New Republic has marshalled evidence that it could happen. At least, she writes, Alabama Senate candidate Roy Moore’s climate change denial was one (of many) turnoff for voters in December.

Whether voters will gain a deeper understanding of the connections between pollution, race and poverty — and vote on them — remains to be seen.

Environmental justice is a real-life problem that stings many Alabamians. It was the poor black community of Uniontown, Ala., where a landfill was receiving the coal-ash from the Tennessee Valley Authority’s 2008 spill at its Kingston Fossil Plant in Tennessee. Their eventual vindication in a 2017 court settlement was inspiring and empowering.

Environmental justice activism on coal ash has spread among several southern states. How such forces might impact the 2018 mid-terms remains unknown.

The open Michigan governor's seat being vacated by term-limited Rick Snyder is still reverberating from the fallout of the Flint water scandal, which weakened the once-iron grip of the GOP. The Enbridge Line 5 pipeline that crosses the Straits of Mackinac (and threatens the Great Lakes) could become an issue.

One thing is certain, whether voters perceive it or not: Trump’s Environmental Protection Agency has yet to fix the “lead and copper rule” at the root of the Flint crisis (much less to fund lead pipe replacement). That could become a problem in the many midwestern and rust-belt districts (many in Trump territory) that have lead problems as bad as Flint’s.

Regional differences affect issues like offshore drilling

The impact of the environment and energy on 2018 elections will depend very much on regional factors. Those forces may prove strong.

One illuminating example is offshore drilling. You will not get elected by opposing offshore drilling in Louisiana, where it means jobs. But Florida (where beaches mean livelihood) is a different matter. President Trump’s January 2018 plan to drill almost all offshore U.S. waters prompted loud, immediate opposition from Florida Congress members of both parties. It was loud not just from Democrat Bill Nelson, but from Republican Marco Rubio.

That pattern can be found in many other states along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, where offshore drilling has been political anathema for decades — California, Oregon, Maryland, New Jersey, Maine, Delaware, North Carolina and others. Election of Congressional candidates in 2018 may depend on how hard they run against Trump’s drilling plan.

Energy development doesn’t cut the same way in every state. In Alaska, the prospect of offshore drilling and opening of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge is politically popular. A majority of Alaskans may vote pro-Trump and pro-GOP; but Alaska’s delegation is already Republican.

Texas may be far more interesting. It has been majority GOP and pro-oil for a long time. But today, its economy depends more on renewables like wind than it once did — and there is even talk that demographic change will push more districts into the Dem column.

In Texas’ variegated 21st district, for example, a Democrat “science nerd,” Derrick Crowe, is making a credible bid for the seat of climate denier Lamar Smith, retiring chair of the House Science Committee. He’s campaigning on climate.

The politics of fuel (or, today, energy sources) has long been a factor in U.S. elections and legislative struggles. Trump, in 2016, went all-in on coal, oil and to a lesser extent nuclear. The pro-coal campaign at EPA and DOE will certainly win Republicans some votes in West Virginia, Virginia, Pennsylvania and Kentucky.

But there is also the risk that all those underemployed miners will realize that they are getting little (not jobs, not wages, not pensions, not healthcare and not safety) from the Trump program. The realization may take a little longer in western mining states like Wyoming.

Evidence is still scant that the Trump-GOP energy program will help actual workers rather than investors and donors. If it’s about jobs, then the solar and wind workers may well outvote the coal and oil workers. That could be a game-changer.

Joseph A. Davis is a freelance writer/editor in Washington, D.C. who has been writing about the environment since 1976. He writes SEJournal Online's Issue Backgrounders and TipSheet columns, directs SEJ's WatchDog Project and writes WatchDog Tipsheet and also compiles SEJ's daily news headlines, EJToday.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 3, No. 2. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement