SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

BookShelf

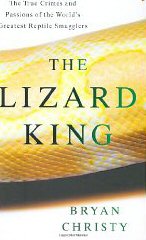

The Lizard King: The True Crimes and Passions of the World's Greatest Reptile Smugglers

By Bryan Christy

Twelve, Hatchette Book Group, New York, 2008

Paperback edition $13.99

Reviewed by CHRISTINE HEINRICHS

This is a book about passions and the men whose souls are gripped by them: the passion to collect rare animals, the passion to make money, the passion to defend wildlife and collar the criminals.

Lizard King author Bryan Christy, an SEJ member, gives a good guys-bad guys account of reptile smugglers and the special agent who chased them. The bad guys are so crafty, ingenious, charming and lacking moral inhibition that only the arrival of an equally determined good guy can match them. It’s a great story, the best kind for journalists, because it’s all true.

The book’s modern-day characters include U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Special Agent Chip Bepler and Mike Van Nostrand, who ran a smuggling network out of South Florida. But Christy’s story begins in the 1940s, long before public interest in biodiversity took hold, when Van Nostrand’s father Raymond was a boy who loved reptiles. A natural salesman and shyster, Raymond was making money before he was out of high school and became involved in supplying zoos and smuggling reptiles.

Raymond was willing to supply other things, too, like cocaine. Eventually, he was convicted on drug charges and sent to jail, though he went on to give evidence against a smuggling kingpin. His son Mike, less attracted to illegal activity than his father, was studying accounting when his father was sent to prison but reluctantly took over the family business. His knack for numbers turned the reptile and cocaine business his father had run out of the garage into Strictly Reptiles, the dominant wholesale reptile business in the nation. The company was part legal and part not.

Enter Bepler, the U.S Fish & Wildlife Service agent. Bepler had gained his love of wildlife through catch-and-release fishing with his father. Sometimes they brought fish home to raise in a pond. After earning a degree in marine biology, Bepler got a job with NOAA, monitoring tuna boats for dolphin bycatch. Though NOAA’s rules don’t allow its monitors to do anything but observe, that didn’t stop Bepler from donning a wet suit and diving down to help dolphins escape the nets.

Tired of life on tuna boats, Bepler joined the Fish & Wildlife Service and was assigned to New York, where he learned the subterfuges of reptile smugglers. Techniques included taping the legs of tortoises together and balling them into socks, hiding snakes in false crate bottoms and secret compartments in luggage, and packing rare species in with legal ones. “Importers tested your knowledge, counting on you not to know whether fifty dirt-covered baby tortoises were all Indian star tortoises, Burmese star tortoises, or Madagascan plowshare tortoises — a crown jewel in the smugglers’ world,” Bepler said. Rare Gray’s monitor lizards were unlikely to be found under fifty legal jumping and biting Tokay geckos.

“Bepler had a vision, a willingness to look at all of the wildlife crime going on in the United States and ask, ‘What is the engine, and how do I stop it?’” Christy writes. But Bepler’s work on barn owls and alligators got laughed at by federal attorneys in New York who were making racketeering cases against John Gotti. Bepler saw that he’d have to take down Strictly Reptiles on Van Nostrand’s home turf, South Florida.

Bepler transferred from New York to Miami — one major wildlife entry port to another. The new South Florida assignment was like “Siberia with mosquitoes and paperwork,” Christy writes. The tale of how he caught Van Nostrand is as compelling as any suspense bestseller. Tough interviews with mules who agreed to turn over evidence, dogged surveillance and teamwork with foreign law enforcement officers gave Bepler enough evidence to raid Strictly Reptiles’ warehouse. At the same time, raids were executed on Van Nostrand’s partners in New York, North Carolina and New Mexico, plus 10 locations in the Netherlands and two in Indonesia.

Van Nostrand decided to cooperate in exchange for a lighter sentence. He served eight months and his information helped take down many other South Florida reptile smugglers. The ripple effect of major U.S. arrests resulted in arrests around the world of other conduits in the global smuggling operations.

After Bepler made the case against Van Nostrand, he went on to join Fish & Wildlife’s special operations team, going undercover to find other ways to stop the illegal wildlife trade engine. But three months after he completed training, he was diagnosed with glioblastoma multiforme, an aggressive brain cancer. He died 25 months later.

Van Nostrand spoke at Bepler’s funeral, describing him as a good father and tenacious investigator. He told the mourners if Bepler hadn’t come down from New York, he never would have stopped smuggling and realized the error of his ways. “I’m gonna miss him,” he said.

Strictly Reptiles is still in business in Florida, trading in insects and other invertebrates such as scorpions, hermit crabs, spiders, centipedes and some small mammals, such as rare gerbils, hedgehogs and sugar gliders. The list of rare species is long. I wrote the names down while reading this book, looking up critters such as tuataras and Sandy Cay Rock iguanas. These creatures are beautiful and exert a powerful appeal, and it is unfortunate that illustrations were not included in this book.

Christy found great material and did it justice. I miss all the characters in it already and look forward to his next book.

Christine Heinrichs is author of two books on traditional breed domestic poultry but is turning her attention to marine mammals on California’s Central Coast.

* From the quarterly newsletter SEJournal, Spring 2011 issue.

Advertisement

Advertisement