SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

TipSheet: Under Pruitt, Watch Enforcement Data

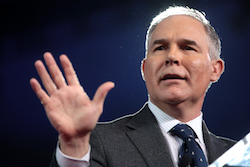

As Scott Pruitt settles in as administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, a major question is what will happen to enforcement of the nation’s environmental laws.

|

| U.S. EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt speaking at the 2017 Conservative Political Action Conference in National Harbor, Md. on Feb. 25. Photo: Gage Skidmore, Flickr Creative Commons |

So it is a very good time for environmental reporters to keep an eye on EPA’s exhaustive enforcement database — whether for local stories or national trends.

Enforcement and Compliance History Online, or ECHO, is an online, searchable database that helps you ask and answer key questions.

Assuming that it survives, that is. Despite bold talk by Trump transition officials about decimating the agency, environmental laws will likely stay on the books. Pruitt told the Senate Environment Committee that he would enforce them.

Environmentalists find some reason to worry about whether he will do so. As Attorney General of Oklahoma, Pruitt disbanded the state’s environmental enforcement unit, folding it into his “federalism” office. Pruitt has complained that EPA has been overzealous in enforcing regulations.

Finding bad actors

The ECHO database is imperfect. But it is also a powerful tool for investigative journalism. You can learn a lot about its capabilities by just exploring. It saves you the time of looking for a needle in a haystack, and allows you to add the numbers up and summarize.

For one thing, ECHO makes it pretty easy to find the bad actors — companies with serious ongoing violations of pollution laws. It shows formal and informal enforcement actions, and whether a facility is in compliance. And it shows these things over a significant period of time, often five years.

ECHO allows you to customize your query to the geographical area of your choice: national, state, local or ZIP code. It allows you to limit your search to air, water, hazardous waste or pesticides. It lets you focus only on facilities in a single industrial category (e.g., petroleum refining). It allows you to see whether enforcement actions have been followed up on. When bad actors come into compliance, it tells you that, too.

EPA’s OECA has also over many years issued annual reports summarizing its enforcement performance. Find them here.

Tracking data trends

Tighter integration of ECHO with other EPA databases in recent years also makes it much easier to track not just facilities, but companies. For instance, ECHO is linked to EPA’s Facility Registry Service. The FRS offers uniform identification of facilities across EPA regulatory programs and helps you follow all the plants operated by a single company across the United States.

A search on Koch Industries, for example, returns some 225 facilities ranging from petroleum terminals to paper mills. The FRS can help you track parent companies of the companies you are looking at.

Importantly for the coming years, ECHO allows you to examine trends in enforcement and compliance. It might even help us tell whether as administrator Pruitt is letting polluters slide.

ECHO will, for example, let you look at enforcement and compliance trends in Oklahoma over much of Pruitt’s tenure as AG there. Oklahoma’s air record is here and its water record here. But what it won’t tell you is what the trend data mean.

A reminder: No data are perfect, and journalists should always do their best to “ground-truth” what the database says. Data are only meaningful in context, and that means data are only an adjunct to good, basic shoe-leather and phone-call reporting and an understanding of how government works.

Even worse: EPA admits to many known problems with its data. ECHO lacks up-to-date air enforcement data because of chaos in the air databases on which it depends. The good news, in some cases, is that EPA gets data from the states, and states sometimes can give you something better from their own databases.

A key is understanding enforcement

You will not be able to make much sense of EPA data unless you work to understand the complex system by which environmental laws are enforced. First of all, much of the enforcement is already being done by the states — to whom EPA delegates primary enforcement authority under most of the main environmental laws.

In the limited number of cases where states fail at enforcement, EPA does take primary authority. You would not know it from listening to Pruitt, but it has been this way since the early 1970s. And there have been struggles over the balance of power between the feds and the states for that long, too.

Remember also that much environmental enforcement does not involve charging a facility in court with violations. The “jack-booted thugs” of GOP legend were replaced with a “compliance assistance” philosophy during the Reagan years. EPA officials, often at the regional offices, work with companies to hammer out reasonable air and water permits, do sometimes-infrequent inspections and ask polluters to pull up their socks when they come up short. Only the most egregious cases go to court.

When pollution cases do go to court, EPA often refers them to the Justice Department’s Environment and Natural Resources Division, which does the actual prosecution. The assistant attorney general in charge of that division makes a huge difference. Obama’s ENRD enforcer, John Cruden, resigned in January. The post is currently held on an acting basis by Jeff Wood, a former energy lobbyist.

Remember also that few if any EPA enforcement cases end with CEOs going to jail. Many cases are settled by a negotiated “consent decree” agreed to by both polluter and prosecutor. Sometimes the main outcome is that the polluter agrees to stop polluting. And often the fines in these cases are dwarfed by agreed-upon investments in pollution control.

Here are a few additional things to look for:

- How long will the EPA’s permanent post of assistant administrator for enforcement and compliance assurance be left vacant?

- Whom will President Donald Trump appoint?

- What are that person’s background, predilections and conflicts?

- Will the Senate Environment Committee grill the appointee rigorously before it votes on confirmation?

- What will the budget of the Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance, or OECA, be in coming years compared to the past? Media have reported rumors that the Trump/Pruitt administration would flat-out abolish the whole OECA.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 2, No. 9. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.

Advertisement

Advertisement