SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

Special Report: Part Four

By LEE AHERN

|

|

|

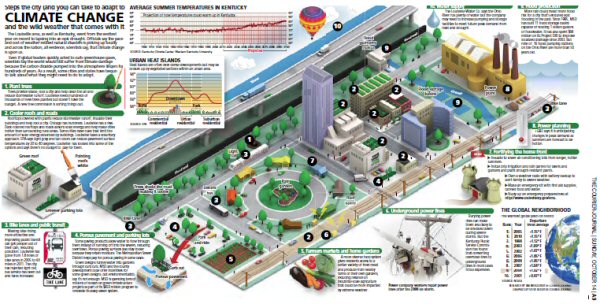

News that focuses on adaptation assumes the existence of climate change, in turn helping change public attitudes and opinions on the topic. Above, a detailed infographic from The (Louisville) Courier-Journal in Kentucky looks at how the community can adapt to climate change. Designer Steve Reed worked with reporter James Bruggers on the graphic, which was part of a three-part series on climate adaptation in Kentucky and Indiana. |

To adapt is to change in response to new environmental conditions. If ever there was a time for humans to adapt it is now — in multiple ways.

Although uncertainty remains when it comes to specific climate impacts on specific regions, the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report makes it crystal clear that global warming is human-caused and severe negative impacts are inevitable. Searise of three feet by 2100 is now predicted with scant prospect of individual behavior or public policy changes stemming the tide.

The planet is moving inexorably toward an era of climate adaptation, a fact with massive implications in a number of areas, including communication. While the need for humans to enter a phase of climate-change adaptation is a very bad thing, changing the focus of climate-change messages from prevention to adaptation may be a very good thing.

Apart from the necessity of communicating issue-specific adaptation information to the public, there is reason to believe that adaptation messages will be seen as more important, credible and persuasive, and that they could be significantly more effective in changing attitudes, beliefs and behavior.

From a rhetorical point of view, prevention messages are problematic. Inevitably, these messages argue that costly steps are necessary because of the near certainty of negative future impacts if current individual behaviors and public policies don’t change.

The problematic words are “argue,” “near” and “future.” These words provide key rhetorical openings for climate-change deniers.

Leaving the terrain of the deniers

Firstly, anytime an argument is made, an alternative or opposing viewpoint is implied (and invited). When the argument includes qualifiers (like “near”) and hypotheticals (like “future”), opposing forces have contested rhetorical ground on which to fight.

New York Times columnist Andrew Revkin calls such messages the “terrain of the deniers.” He pointed out in a recent blog post that the tendency for journalists to focus on current events in proximal locations (standard determinants of newsworthiness) often results in greater issue uncertainty and opens the door for counter-arguments.

The primary example is stories that link current weather events to global warming. Because the connection between global warming and any one local weather event is extremely weak, it is easy to cast doubt on the entire idea of long-term human-caused climate change.

While prevention messages need to argue a link between current behaviors and policies and future impacts — links that always contain a least a crumb of uncertainty — adaptation messages make no such leap. Rhetoric opposing prevention messages just needs to argue that something might not happen. With adaptation messages, opposing rhetoric must argue that something is not happening. This is much more difficult. When people are witnessing the impact in their personal lives, it is nearly impossible.

Tapping into favorable news values

Although the rhetorical advantages of adaptation messages are important, they are by no means the end of the story. You can win an argument and still fail to convince your opponent you’re right.

People hold their opinions and attitudes for a variety of reasons. They may have attitudes for ego-defense, or to express their identity to others. According to some researchers, people don’t even know (consciously) why they have the attitudes they do (see the work of Philip E. Converse). When asked, people will make up a reason for their opinion, but in reality the opinion comes first, not the rationale.

This kind of on-the-fly attitude formation is seen as guided by more deeply-held values and worldviews. A particular individual might not know much (or have an attitude about) a specific economic policy, but he or she probably has a broader worldview (economic conservative or liberal) that will underlie his or her opinion formation about it. This makes values and worldviews extremely important when it comes to attitude formation and change.

Herber Gans explored how critically important social values form the subtext for modern journalism. When a reader consumes news, he or she is not just taking in the specific issue information on the surface of the article. The reader is also absorbing the news values implied by the text. Indeed, these implied news values are often more important to attitude formation and change than surface information and rhetorical arguments.

In an example provided by Gans, a story about a politician being arrested for corruption implies the values that corruption is unethical and politicians should be accountable for their actions.

Analysis at the level of news values makes the contrast between prevention and adaptation messages even more fundamental. Adaptation messages assume the reality and existence of climate change. A story about the need to build higher storm walls around metropolitan areas implies that sea levels are rising (present tense). There is no argument about what is likely to happen (future tense) for opposing rhetoric to contest. Even more importantly, there are no elements in the message for the receiver to counter-argue.

The news-information environment is a vital dimension of the culture in which audiences live. And culture is incredibly important when it comes to the development of personal values and worldviews. The same way humans learn to adapt to a changing physical environment, they learn to adapt to changing information environments.

A telling recent example has been the growing acceptance of gay marriage. At the beginning of the gay rights movement, much of the messaging and rhetoric emphasized arguments about equality and fairness, to little effect. But as more and more news information (and, importantly, entertainment) began to imply that gay marriage is acceptable, to assume marriage equality as an accepted value, public attitudes and opinion began to change.

When warming is a given

A news-information and entertainment environment (the lines between these are becoming blurred) where adaptation is the dominant theme in messages related to global warming moves from the terrain of the deniers and reinforces the value that climate change should be addressed as a current and concrete threat.

The impact on audiences of living in such a media environment will very likely be an increase in attitudes, beliefs and behaviors that support sustainability and environmental protection. Over time, changing public attitudes will also positively impact public policy.

But aside from these macro-level effects, adaptation messages are likely to be more persuasive at the individual, psychological level. Advertisers have known for decades that the best way to convince an audience of something is not to argue with them. The psychological term for it is “reactance,” which is the idea that people tend to scrutinize and counter-argue any information presented to them as “new.”

Reactance is especially strong if people are being asked (or told) to do something. (This is why reverse-psychology works: if reactance is strong enough people will do the opposite of what is being asked.) This general psychological reaction makes intuitive sense from an evolutionary perspective. Precious energy and cognitive resources would not be wasted on recognized stimuli, only on the novel, new or unexpected.

There is a schoolyard trick that works every time: ask a group of people to shout out the answer as soon as they know it to the question “How many of each species did Moses put in the ark?” Inevitably, the group shouts “two” in near unison. After a pause, people begin to chuckle at the realization that they were just duped. Noah was the guy on the ark, not Moses. (This works much better in person than in print.) Why is it so easy to catch people with this kind of trick? Because “given” information is not scrutinized. In this example, the new or unknown information was about the number of animals. The fact that Moses was putting them on the ark was just a given.

In adaptation messages global warming is a given and therefore its existence invites no scrutiny.

Along similar lines, media scholar Neil Postman explored the strong and subtle persuasiveness of information that just “is.” In a classic example he talked about a McDonald’s TV commercial where there is no information or argument about the quality or price of the food, just images of a man and his daughter eating hamburgers in the park and visiting a zoo and having a lovely day and being happy. There is no agreeing or disagreeing with the images, they just are. It is just a matter of liking or not liking McDonald’s. And because McDonald’s clearly makes people happy, why wouldn’t you like it?

Adopting adaptation

Among environmental and science communication scholars and practitioners, there is a growing consensus that the “deficit model” has failed. This was the appealing idea that people simply have a lack of information and understanding about global warming and by filling up this knowledge deficit, attitudes, beliefs and behaviors would change. It is now clear that it is much more complicated.

As the foregoing review suggests, there needs to be an emotional subtext that moves people. As one advocate at a leading global environmental group told me at a recent conference, “It is all about emotion. That is where everyone is going.”

While adaptation messages are not any more inherently emotional than prevention messages (they certainly could be made so), they do have some other elements that give them more impact. By adopting adaptation as a primary theme in global-warming messages, audiences will be less critical and more accepting of implied pro-environmental values and opposing rhetoric will have fewer opportunities to sow doubt.

A world of global-warming adaptation is not desirable, but adaptation messages are.

Lee Ahern is assistant professor of advertising at Penn State College of Communications, senior researcher at the Arthur W. Page Center for Integrity in Public Communication and chair of the International Environmental Communications Association.

Back to the Special Report main page.

* From the quarterly newsletter SEJournal, Fall 2013. Each new issue of SEJournal is available to members and subscribers only; find subscription information here or learn how to join SEJ. Past issues are archived for the public here.